Fresh Batch #125: The Name of God is the Holy Spirit of Language

Vowel Omissions & Changes

Merry Christmas and Yuletide, and if you don’t celebrate those, I hope you’re still enjoying in the festivities through the spirit of gratitude and embracing the gift of life you have, whether it’s enjoying the world in solitude or with your loved ones, however you choose, and whether you like Santa or Krampus, all that matters is you be good to each other. Salut!

One of the things that happens to language as it evolves, or devolves depending how you look at it, is the omission of letters, bet it at the beginning or middle of a word. Those unaware of this process will find examining language for the purpose of discovering history or chronology a fruitless endeavor. The following examples of initial vowel omissions are from Edward Lhuyd (Archaeologia Britannica, p. 11), published in 1707 AD. These will serve as excellent references should you find yourself having to defend your position in these matters.

Lhuyd wrote (Ib.), “A in the diphthong AE (Æ) was frequently omitted by the Romans, in any part of a word; as appears by divers inscriptions, as also I in IE; and V after Q.”

That means when Esar is used, Aesar is likely meant, i.e., Sol, in Hestrusca etiam lingua Esar vocatus est, meaning the sun was called Esar in the Etruscan language, thus Aesar, the Etruscan and Irish word for God, is also the same as Esar, the Etruscan word for the sun, which is also used as plural for gods in the Gothic, hence the Aesir. This is indicative of the sun and God being linked, or the sun being the mediator of God, and the gods being aspects of the sun at different times of the year. I didn’t come to this conclusion on a whim. It’s in the language of our ancestors.

Next, Lhuyd observed vowels omitted in the termination of words. He wrote, “In our Modern Orthography of the English, the Final Vowels formerly us’d, are in divers words omitted: Especially A and E.”

He gave the examples of crystalla and crystal, hana and hen, steda and steed, assa and ass, hara and hare, wrenna and wren, leca and leech, fourtha and fourth, fiftha and fifth, treou and tree, hnutu and nut, the Welsh kuru (ale) and Cornish kor, and the Welsh Lhiu (color) and Irish Li.

Next are labial mutes omitted, such as in words like Ptolemy, the P not being pronounced, thus muted.

The omission of labials in the middle of words is definitely an improvement in terms of speaking the language, but not in terms of trying to discern the origin of the words.

There are quite a few words where initial palatal letters in words shared by these similar cultures that were omitted, which, if accurate, demonstrates that it’s not just something that happens in younger languages. It goes both ways if there is any interaction between the cultures, probably because it is the path of least resistance in terms of learning and being able to speak a foreign language.

Lingual mutes are also omitted in the middle of words, i.e., the Latin word argentum and the Welsh words arrian and arriant, which pertain to silver. I wonder if this is anecdotal or if there is any connection to Aryan.

Lingual mutes in the middle of a words are apparently how we get words like Lent, which occurs in spring, from Lengten, the spring. It’s essentially the same word as lengthen, perhaps related to the lengthening of the days that is much more noticeable during this time of year.

There are other examples of this, but I am not fluent in Welsh, Cornish, Armoric, or Irish, so unless something jumps out at me, those interested in the subtleties can read the entire work themselves and go through it with more detail. The point of bringing this to your attention is to demonstrate how languages deviate and appear to be much more different than they are, but when acknowledging the changes, the languages were originally much more similar to each other and aligned with the source(s) of their origin. There are so many examples of words being the exact same to those who acknowledge these patterns, for example the Welsh aradr, a plow, and the Middle French araire, meaning the same, and the Latin aratrum.

Also, this pattern is responsible for words like Cyning and King, but take a peak at how Northumberland and Oxford used to be written.

Lhuyd added (Ib. p. 12.), “We find the Letter N very frequently omitted in Roman inscriptions, but whether for Brevity in writing, or because omitted also in vulgar Pronunciation, is not easy to determine.”

In looking at lingual mutes omitted, I noticed it happened for the Welsh and Irish word for bird, the Welsh word being eden. Is this anecdotal or could there be a connection to the Garden of Eden being the Garden of the Bird? Which bird?

Many types of birds have represented the sun, and aspects of it at different times of the year, to different cultures, such as eagles (phoenixes), falcons/hawks, doves, peacocks, pelicans/storks, etc. Are we looking at a hidden way of saying the Garden of the Sun? As the variation of vowels is understood, Eden is Adon, or Lord, hence Adonis, which predates any of the scriptures. Thus the Garden of Eden is the Paradise of God, or Among the Stars of the Lord, which will be explained.

Keep in mind the relationship with Ave Maria, with ave also signifying bird in Latin. Maria means seas, or in other words, Bird of the Seas, or Wanderer of the Seas, the Pelasgos or Navigator.

Recall the description of the territory allotted to darkness, or the winter months, in the Book of Jubilees that I wrote about in July’s End with Black Swans, “And for Ham (blackened; darkness; winter) came forth the second portion, beyond the Gihon (gushing forth; described as encircling the entire land of Cush, who begat Nimrod) towards the south to the right of the Garden (of Eden), and it extendeth towards the south and it extendeth to all the mountains of fire, and it extendeth towards the west to the seas of ‘Atêl and it extendeth towards the west till it reacheth the sea of Mâ’ûk—that (sea) into which everything which is not destroyed descendeth.”

Again from July’s End with Black Swans, the etymology of Paradise, which I learned from a clergyman, is a detail that is evidence of the scriptures being written in Latin first (or by people with a Latin mindset writing in Greek and Hebrew), “Paradise comes from the Septuagint translation Παράδεισος (Paradeisos). The phonetic cabala reveals it is divided into para-diis, which conveys among the stars. Diis is the plural form of deus, meaning gods. The Garden of Eden is Paradise, Heaven, among the gods, which are the stars because the scriptures were written by watchers, seers, bishops, who are the astronomers and astrologers of their time.

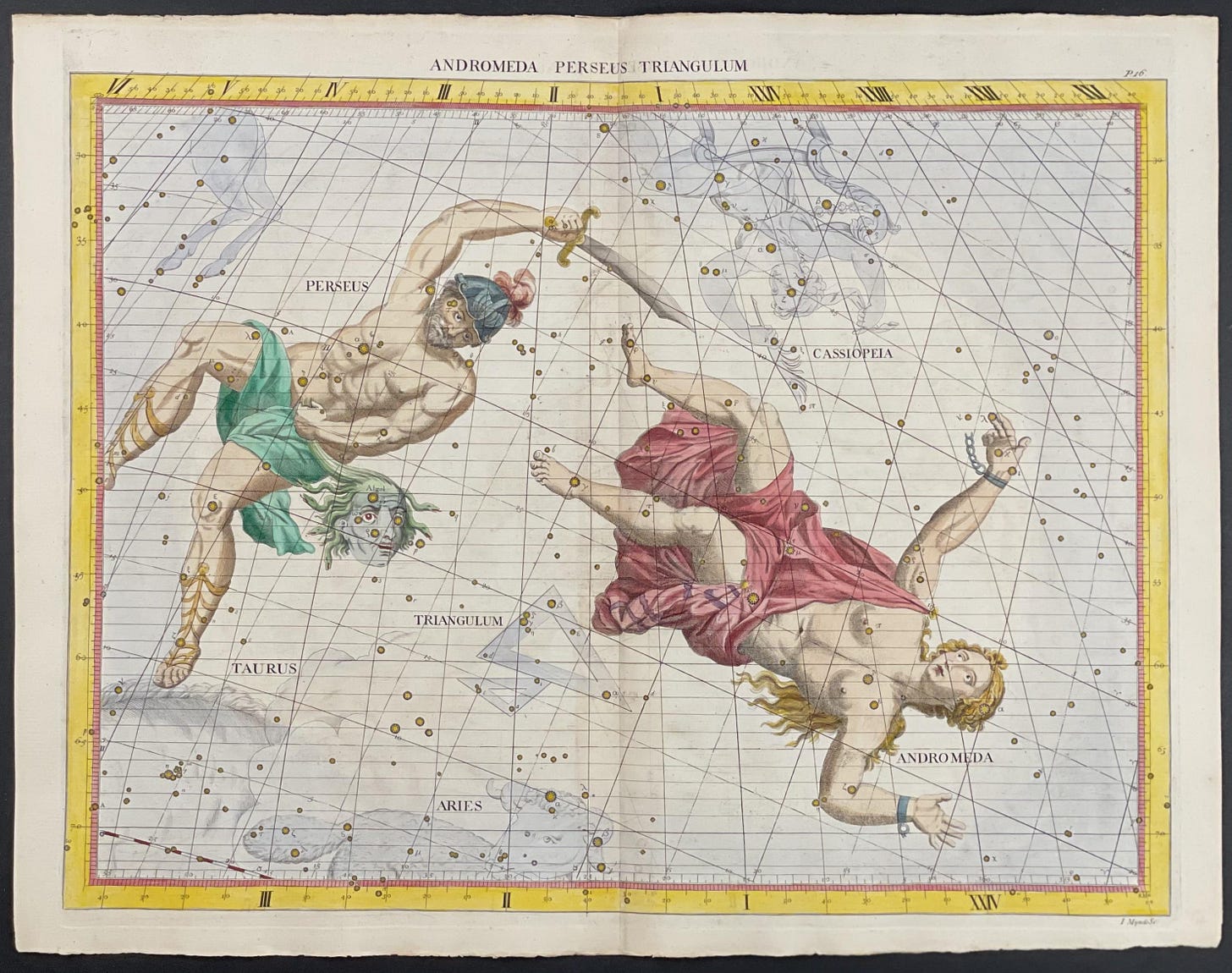

“On the eastern side of paradise there is a constellation Perseus, which is the astronomical drama playing out that we read about in mythology and in Genesis 3:24, ‘So he drove out the man; and he placed at the east of the garden of Eden Cherubims (it should just be Cherubim, as the -im indicates the plurality of Cherub; the citation was from KJV), and a flaming sword which turned every way, to keep the way of the tree of life.’

“Perseus is a constellation above Taurus, spanning 28 degrees of the Zodiac in the signs of Taurus and Gemini. Gemini is made up of the little children, Castor and Pollux, the Cherubim. When Perseus is in the east of the Garden of Eden, Virgo, Boötes, and Serpens are in the west of it. The Garden of Eden is the starry sky. Perseus rises as Adam and Eve fall (or set). Who is Adam? He is none other than Boötes. Who is Eve? She is Virgo, just beneath Adam, or Boötes. The serpent that tempts them into the fall is Serpens.”

The eastern constellations of the Zodiac are in spring time, when the sun is rising from winter above the equinox. The easternmost point would be the boundary between the constellations of Pisces and Aries. The following painting is kind of tricky to read if you’re unfamiliar with the system, but imagine it is a sphere of heaven, or the band of the ecliptic that composes the Zodiac, along with the other constellations north and south of it, unwound into a straight line rather than a ring or dome. If you zoom in, you’ll see three latitude lines. The middle is the equator and the other two lines are the tropics. The constellations above are the northern constellations, the ones below are the southern constellations. From left to right, you’ll see the Zodiac beginning with the twins of Gemini, then Cancer, Leo, Virgo, Libra, Scorpio, Sagittarius (the southernmost constellation in the Zodiac), Capricorn, Aquarius (pouring his urn into the mouth of the southern fish: the Royal Star Fomalhaut), next is Pisces, and finally Aries and Taurus, which are touching each other (it looks like an artistic choice to make the ram look like the lower half of the bull), so it’s hard to make out the ram from this small photo. On the far right, you’ll see the feet of the twins cut off by the clouds, signifying the continuation of this pattern or path and how the right portion of the sky relates to the left portion.

The stars move like birds in a flock. Could the ancient Britons’ naming of birds be based on stars, or could the Garden of Eden be based on the Welsh word for bird (eden)? If these subjects intrigue you, dive into Spirit Whirled and get brought up to speed.

Become a member to access the rest of this article.

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to Ancient History, Mythology, & Epic Fantasy to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.