Fresh Batch #141: Amplitude & Declination

Garnished with Cornish & served with a side of Black Swan

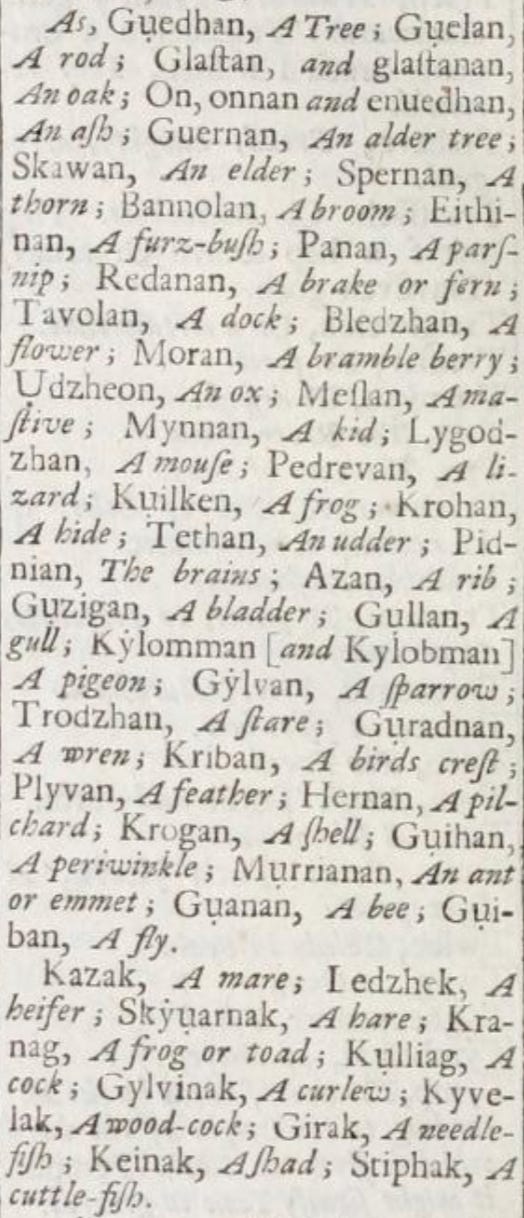

I suspect that I, or others, will find keys to the ancient Italian languages embedded in the remains of languages in Northwestern Europe. The last few articles focused on Cornish, which will continue in this one. Edward Lhuyd wrote (Arch. Brit. p. 240.), “The most common Termination of the names of Natural Bodies in in, an, or en, and sometimes on; and not a few of them do also end in K, or G.”

Again (Ib.), “Nouns Official or Appellations of Tradesmen, or Men of any Employment, and other metaphorical names, derived from them; end generally in r; but sometimes also in k, and sometimes in s, or (as anciently) in t, or d.

“Such Nouns when of the Feminine Gender, are commonly formed by the addition of es. As Seuyades, A woman-taylor; Felores, One that plays on the Violin; Portheres, a woman-porter; Pechadyres, A sinner; Pestriores, A witch; Enevales, A she beast.

“We have already observed in the first Title of this Volume, p. 27. col. 2. and 28. col. 1. that d and t in the Welsh, are changed to s or z in the Modern Cornish. And this rule is so general in the Termination of Nouns, as appears by the instances there inserted that it very rarely fails, unless, as above excepted, in old Manuscripts.

“The Nouns that terminate in w [or u] in Welsh, end commonly in o, in the Cornish. (The first bold-italic word will be Welsh, the second Cornish, with the meaning in the middle of them.) As Karu, A stag, Corn. Karo; Taru, A bull, Taro; Guedhu, deprived, Geudho; Xueru (Chueru), Bitter, Huero; Medhu, Drunken, Medho; Maru, Dead, Maro. (I’m not sure if there is any connection to the Phoenician Maur (Great, Lord, or Prince), the Indian Meru, the Latin Mare (Sea), or the Etrusco-Latin Mars.)

“The Cornish Nouns that agree with the Latin, never terminate in a Vowel, but generaly in the Penultimate or else in the last Consonant of the Latin; or at least in a Consonant of the same Class; As appears by the following examples.”

“The Genders of Nouns are two: The Masculine and the Feminine.

“All proper names of Men, and the appellations of all Tradesmen and Men of any Employment or Profession are of the Masculine of course. And so are the names of Winds and of the Months; of the Senses, of Virtues and Vices; and of Metals.

“All proper names of Women and appellatives of their employment; as also the names of Countries, and of Rivers, and of Towns, Villages, and Churches, are of the Feminine.”

When it comes to the gender used in the naming of wild beasts wild beasts, the big ones are masculine in gender and the small ones are feminine. The names of birds are based on their nature, with the dominant ones like Eagles being masculine and the black birds and pigeons being feminine. Fish are generally masculine. The names of insects are mostly feminine, as are trees.

Labials P—B, B—V, M—V, F—V, and R sometimes

The Cornish terminates basically two ways for singular and plural.

The -ou termination doesn’t indicate plurality in French, but instead indicates masculine nouns. This same technique is used in Greek last names to indicate patriarchy, but it doesn’t have the same significations when used in other words as it does in French or Cornish. The three of them use -ou for different purposes, so I’m not sure it’s a result of diffusion, but perhaps someone more advanced will correct or contribute in the comments. The significance I see is that the Cornish difference in the -ou termination occurs in a place that is right across the English Channel from Armorica, and it may signify a separation between the two, or, more importantly, it may indicate a separation between the Armoric and the French. This would indicate the Armoric are leftovers from the Etrusco-Phoenicians and their language’s affinity to those of Gaul is a result of diffusion but not origin. However, I will have to revisit the Armoric at a later date to corroborate this.

While there is nothing too exciting or revelatory, we do see the philological interchanges or changes in the Cornish, all of them being common in other languages except for the M—V change, which, in this case, the word for horse, marh (similare to mare) becomes verh (similar to the root of vernal). Marh, a horse, is philologically identical to merh, a daughter, which becomes vyrh. The Latin word for sea is mare, and we affix mer- to words like mermaid, a woman, maiden, or daughter of the sea.

However, V function like a W, and we do see the interchange between those two letters, particularly in Latin and Sanskrit. But I won’t digress. If any of this is new, make your way through the Spirit Whirled series. To see how all of this ties into the bigger picture of European history, read The Real Universal Empire.

Become a member to access the rest of this article.

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to Ancient History, Mythology, & Epic Fantasy to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.