According to Pettigrew, at the time of his work, the catacombs of Thebes were the most elaborate. He wrote (Hist. Egypt. pp. 34, 35.), “Five series of these subterraneous caverns have been described by travellers in Egypt as being in various states of preservation. They are those of Alexandria, Saccara, Silsillis, Gournou (Qoorna), and the tombs of the kings of Thebes. These vary considerably in extent. Those at Thebes are the most extensive. Over these hypogæa were built the city of Memphis and other places. It must be admitted that in the selection of these places for depositing the dead,—places where the water of the Nile could not reach, and where the air could scarcely penetrate, in caverns hidden from the view of men, and hewn out of the solid rock, surmounted by the base of the pyramids,—the ancient Egyptians must have been deeply impressed with the necessity (agreeably to their religious opinions on the subject of the Metempsychosis), and thus made choice of, situations beyond all others calculated to receive and to preserve from decay and corruption the remains of their dead.”

This seems a bit too much for a culture that doesn’t appear to have advanced technology. The more challenging something is, the less likely people are going to do it unless it is a necessity. I love my family, but I’m not going to squander my resources or spend a significant portion of my life to dig a catacomb for an elaborate tomb for each member. I think something else is going on. Either researchers who claim there is lost high technology, that we know nothing about, are correct, or the obsession with Metempsychosis is a smokescreen for cultures to create tombs, which are more akin to vaults for preserving the spoils of war and treasuries. The supposition that these structures were created with primitive soft tools like copper is not viable. Even though people have demonstrated that they can chip away at certain stone and carve into stone using copper or other stones, they’ve never demonstrated the skill or proficiency that is found on the monuments and temples of Egypt, and in a timely manner. I do not claim that people couldn’t get proficient at this primitive carving. However, the time it takes is too long, which essentially becomes a waste of one’s life. It doesn’t add up given the human nature that I’ve experienced.

Pettigrew continued (Ib. p. 35.), “But at Sais the tombs are erected upon mounds of earth; it is not rocky here. So numerous are the masses in the catacombs that they are said to extend to the distance of some miles, even to the temple of Ammon and the oracle of Serapis. The city of Saccara is the nearest to the cave of the mummies, as it has been called, and the inhabitants of Saccara are said to have derived the means of subsistence by breaking open these caves and extracting from them the embalmed bodies. M. Champollion is the latest traveller from whom we have an account of the plain of Saccara, the ancient cemetery of Memphis, which he describes as parsemé de pyramids et de tombeaux violés. (Dotted with pyramids and violated tombs.) ‘This spot,’ says he, ‘thanks to the barbarous rapacity of the dealers in antiquities, is absolutely barren for the student. The highly sculptured and ornamented tombs are destroyed and lie in ruins. The place is frightful, being formed only of mountains of sand strewed with human bones, the remains of former generations.’ (Lettres de Champollion, p. 68.)

One of the most suspicious details about the Great Pyramid is the lack of hieroglyphics. Should the structures be contemporary, it might be accounted for that the casing stones had hieroglyphics, but were striped in order to build other structures. I don’t accept that as of now, but it is an explanation offered by Mr. Salt from the Quarterly Review, who claimed that one of the stones, bearing an inscription of hieroglyphics and figures, is built into the walls (of another temple) upside down, which goes to prove that it had originally belonged to some other building. But there does not appear to be anything definitive on this subject.

Pettigrew continued (Ib. pp. 37, 38.), “The catacombs of Thebes are the most extraordinary and magnificent. The Necropolis, or City of the Dead, of this place, a spot described as ‘devoted by nature to silence and death,’ is situated on the west bank of the Nile, and formed the burial place of the people as well as of the kings. Diodorus Siculus (Lib. i.) mentions that, according to history, there were forty-seven royal tombs at Thebes, of which only seventeen remained at the time of Ptolemy Lagus. (Biban-el-Molouk, the place of the tombs, or rather the Gates of the Kings, is, according to De Sacy, a corruption of the ancient Egyptian name, Biban-Ourôon. This royal Necropolis is situated in an arid valley enclosed by very high rocks. No one tomb communicates with another; they are all isolated. M. Champollion was convinced that they contained the bodies of the kings of the eighteenth, nineteenth, and twentieth dynasties. He perceived the most ancient of all, that of Aménophis-Memnon, in the isolated valley at the west.—See Lettres, p. 221.) In the time of Diodorus Siculus most of them were destroyed. Strabo (Lib. xvii.) says there were forty royal sepulchres cut out of the rock, and that they had obelisks and inscriptions setting forth the riches, power, and empire of the several kings.”

Again (Ib. pp. 38, 39.), “Belzoni has given an interesting account of Gournou, the burial place of the renowned city of Thebes. It is a tract of rocks, about two miles in length, at the foot of the Lybian mountains, on the west of Thebes. Every part of this immense tract is cut out into large or small chambers, each having its separate entrance, and there is seldom a communication from one to the other. According to this traveller there are no sepulchres in the world like them, no excavations or mines that can be compared to them, and no exact description can be given of their interior, owing to the difficulty of visiting these recesses, not to mention that the inconveniency of entering them is such that few would be able to support the exertion. ‘A traveller,’ he observes, ‘is generally satisfied when he has seen the large hall, the gallery, the staircase, and as far as he can conveniently go: besides, he is taken up with the strange works he observes cut in various places, and painted on each side of the walls; so that when he comes to a narrow and difficult passage, or to have to descend to the bottom of a well or cavity, he declines taking such trouble, naturally supposing that he cannot see in those classes any thing so magnificent as what he sees above, and consequently deeming it useless to proceed any farther. Of some of these tombs many persons could not withstand the suffocating air, which often causes fainting. A vast quantity of dust rises, so fine that it enters the throat and nostrils, and chokes the nose and mouth to such a degree that it requires great power of lungs to resist it, and the strong effluvia of the mummies. This is not all; the entry, or passage where the bodies are, is roughly cut in the rocks, and the falling of the sand from the upper part or ceiling of the passage causes it to be nearly filled up. In some places there is not more than a vacancy of a foot left, which you must contrive to pass through in a creeping posture like a snail, on pointed and keen stones, that cut like glass. After getting through those passages, some of them two or three hundred yards long, you generally find a more commodious place, perhaps high enough to sit. But what a place of rest! surrounded by bodies, by heaps of mummies in all directions, which, previous to my being accustomed to the sight, impressed me with horror. The blackness of the wall, the faint light given by the candles or torches for want of air, the different objects that surrounded me, seeming to converse with each other, and the Arabs with the candles or torches in their hands, naked and covered with dust, themselves resembling living mummies, absolutely formed a scene that cannot be described. In such a situation I found myself several times, and often returned exhausted and fainting, till at last I became inured to it, and indifferent to what I suffered, except from the dust, which never failed to choke my throat and nose; and though, fortunately, I am destitute of the sense of smelling, I could taste that the mummies were rather unpleasant to swallow. After the exertion of entering into such a place, through a passage of fifty, a hundred, three hundred, or, perhaps, six hundred yards, nearly overcome, I sought a resting place, found one, and contrived to sit; but, when my weight bore on the body of an Egyptian, it crushed it like a band-box. I naturally had recourse to my hands to sustain my weight, but they found no better support; so that I sunk altogether among the broken mummies, with a crash of bones, rags, and wooden cases, which raised such a dust as kept me motionless for a quarter of an hour, waiting till it subsided again. I could not remove from the place, however, without increasing it, and every step I took I crushed a mummy in some part or other. Once I was conducted from such a place to another resembling it, through a passage of about twenty feet in length, and no wider than that a body could be forced through. It was choked with mummies, and I could not pass without putting my face in contact with that of some decayed Egyptian; but as the passage inclined downwards, my own weight helped me on; however, I could not avoid being covered with bones, legs, arms, and heads rolling from above. Thus I proceeded from one cave to another, all full of mummies piled up in various ways, some standing, some lying, and some on their heads.’ (pp. 156, 7.)

“Captain Light crept into one of the mummy pits or caverns, which were the common burial places of the ancient Thebans. As it happened to be newly discovered, he found thousands of dead bodies, placed in horizontal layers side by side; these he conceives to be the mummies of the lower order of people, as they were covered only with simple teguments, and smeared over with a composition that preserved the muscles from corruption. ‘The suffocating smell,’ he says, ‘and the natural horror excited by being left alone unarmed with the wild villagers in this charnel house, made me content myself with visiting two or three chambers, and quickly return to the open air.’ (Quarterly Rev. No. 37.)

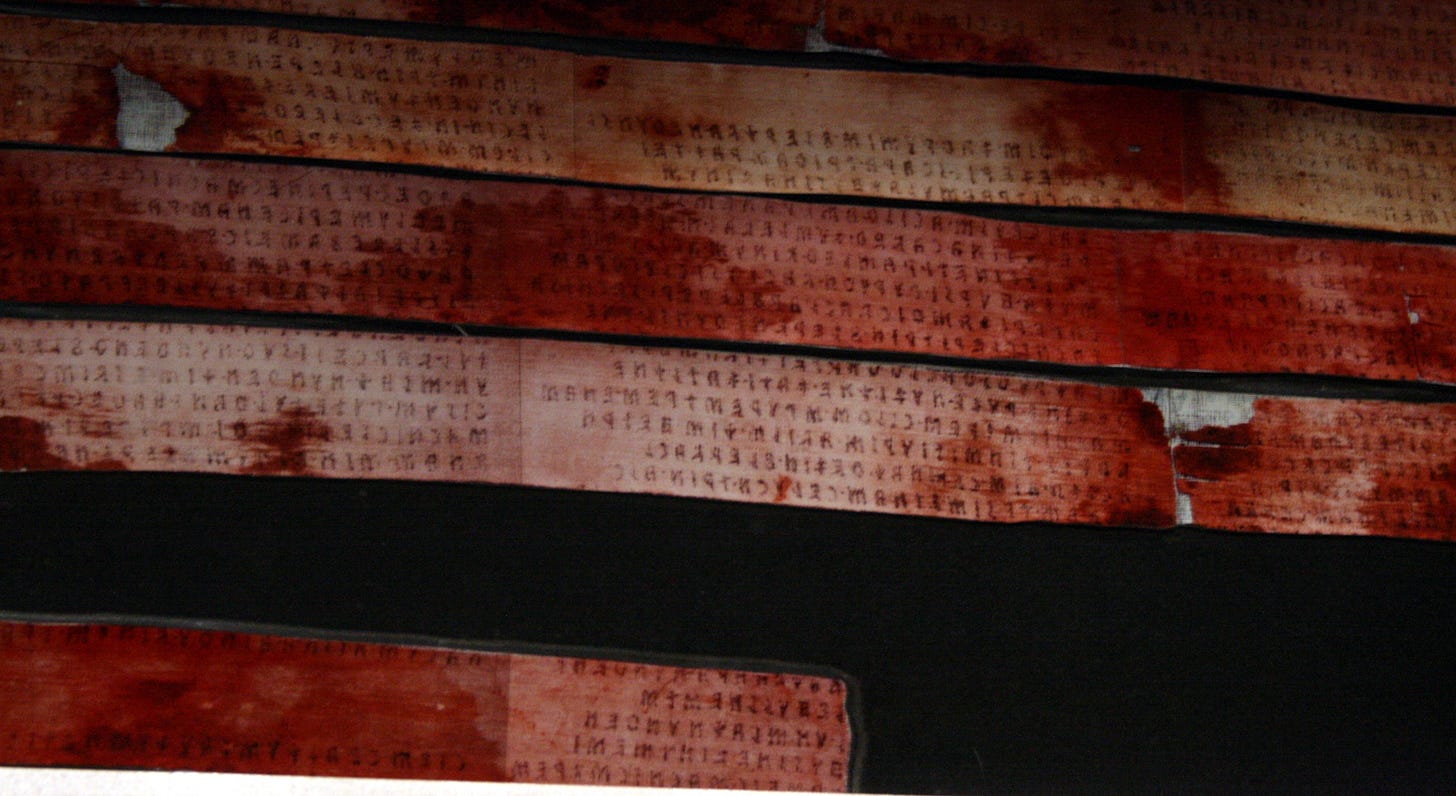

The main reason I’m intrigued by this location is a result of an alleged account from the Greek general Conon, that the Phoenicians once made Egyptian Thebes their capital when they possessed the empire of Asia. The following is the Zagreb mummy, found wrapped in Etruscan script, at Egyptian Thebes (Luxor)!

Everything you know in Europe is derived from this alphabet, not Greek or Hebrew. The way you can demonstrate that is by recognizing that these languages are so old that they can’t be translated. This is because there is no affinity between Etruscan and Greek.

To dive deeper into this work and see how I arrived at my conclusions, read the Spirit Whirled series and then The Real Universal Empire.

Become a member to access the rest of this article.

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to Ancient History, Mythology, & Epic Fantasy to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.