Fresh Batch #167: Porphyry

Purple-clad Roman Architecture in the Great Pyramid of Egypt

Charles Piazzi Smyth wrote (Our Inheritance in the Great Pyramid, pp. 75, 76.), “Had it nothing more to depend on than its external figure, the Great Pyramid might yet be considered as quite unique, both in the purity of its lines and deep meaning of its angles; for though the second and third pyramids of Jizeh (Giza) do somewhat approach it in form,—they have sensible differences and peculiarities of their own; and before we have got very far away from their neighbourhood, we meet with other pyramids, some of them having distinct re-entering angles half-way down their sides; and others which are built in large inclining steps, known as ‘the pyramids of Degrees;’ and others yet again, more like Indian or Mexican creations; and in such strange shapes at last, as to cease to deserve any classical appellation connecting them with the well-known geometrical solid.

“But a more characteristic distinction still, is connected with the interior; for the outside is the mere shell, while the inside is, in a natural history sense, the living being which tenants it; or at least its quasi vital end, or life-important purpose, whose functions may haply be deduced by examination of the minuter features of its abode.”

This portion of the interior was claimed to be all that the Egyptians knew of within a generation after the Pyramid to the present day at the time this book was published. Smyth claimed there was proof that the Romans were once inside the subterranean chamber. He wrote (Ib. p. 77.), “There appears also to be some probability as to the pyramids, with this single characteristic, but of poor workmanship, being indigenous in Egypt before the erection of the Great Pyramid; which in that case, therefore, began in so far, in deference to native ideas: improving that plan, however, so extraordinarily, that it was essentially the Great Pyramid version of it which the Egyptians subsequently repeated in so many of their later pyramids.”

The evidence was provided on page 80, “No doubt tradition and imagination always played large parts in tales of the interior of the Pyramid; but that Romans did once enter that subterranean chamber (Plate VI. Fig. 1) was proved, as we have already indicated on p. 77, beyond a doubt, when M. Caviglia rediscovered it in 1820, and found blackened Roman letters upon its roof.” (Howard-Vyse’s Pyramids, vol. ii. p. 290.)

If any of you have resources of good photos regarding these inscriptions, let people know in the comments. The best I can find is a screenshot from a now defunct site, but the quality isn’t good enough to make out the “Roman letters”:

The implications could be immense if those “Roman letters” turn out to be late-Etruscan letters that Roman ones descended from. A mummy wrapped in Etruscan script was found as far south as Luxor. I’m not making claims. I’m posting this so people with access can be more cognizant of documenting these things. The writing may also have been scraped off to hide history by now. That, or these accounts are erroneous or forgery. Roman letters without a translated inscription is suspicious.

Those who learn ancient Italian alphabets will see that it is easy to confuse them with both Roman letters and Scandinavian/Germanic Runes.

It may be that the Great Pyramid was build upon some preexisting structure, which would account for the rude interior that had a function necessary to life. It’s observable that the subsequent Pyramids did not have the same functions, but were rather imitations of the Great Pyramid, and used as tombs, which caused people to suspect the Great Pyramid was used as a tomb.

Smyth continued (Ib. pp. 77, 78.), “In the second, and also the third Jizeh pyramid, they did indeed attempt (see Plate VIII. Figs. 1, 2) to introduce a certain amount of complication; but it was only useless and confusing complication, without any very sensible object; unless when it was to allow a second king, to make himself a burial-chamber in the pyramid-cellar already occupied by a predecessor, and then it was bad. Gradually, therefore, as the researches of Colonel Howard-Vyse have shown, on the fourth, fifth, sixth, seventh, eighth, and ninth Jizeh pyramids (see Plate IX. Figs. 1, 2), the native Egyptians dropped everything that they had tried except the one, single, partly descending and partly horizontal passage, with a subterranean chamber for burial purposes.”

Al Mamoun’s account seems a bit fantastical, but I’ll include a portion of it because if there is any truth, cyclopean stone implies Etruscan masonry (Tyrrhenians). Smyth wrote (Ib. p. 88.), “Upon no less than 100 feet of the steep incline, crouched hands and knees and chin together, through a passage of royally polished marble, but only 41 inches in height or breadth, they had painfully to crawl with their torches burning low. Then suddenly they emerge into a tall gallery (see Plate XI.); in front of them, on the level, another low passage leading to an inconsiderable room; on the right hand, a black, ominous-looking well’s mouth; and onwards and above them, a continuation of the glorious gallery or hall leading on to all the treasures of the earth. Narrow, certainly, was the way (Abrahamic undertones), only 6 feet broad anywhere, and contracted to 3 feet at the floor; but rising to a height of 28 feet, almost above the power of their smoky lights to illuminate; and of polished glistering marble-like cyclopean stone throughout.”

Smyth cited Sir G. Wilkonson (Ib. p. 97.), “The authority of Arab writers is not always to be relied on; and it may be doubted whether the body of the king was really deposited in the sarcophagus;” and again, “I do not presume to explain the real object for which the Pyramids were built, but feel persuaded that they served for tombs, and were also intended for astronomical purposes.”

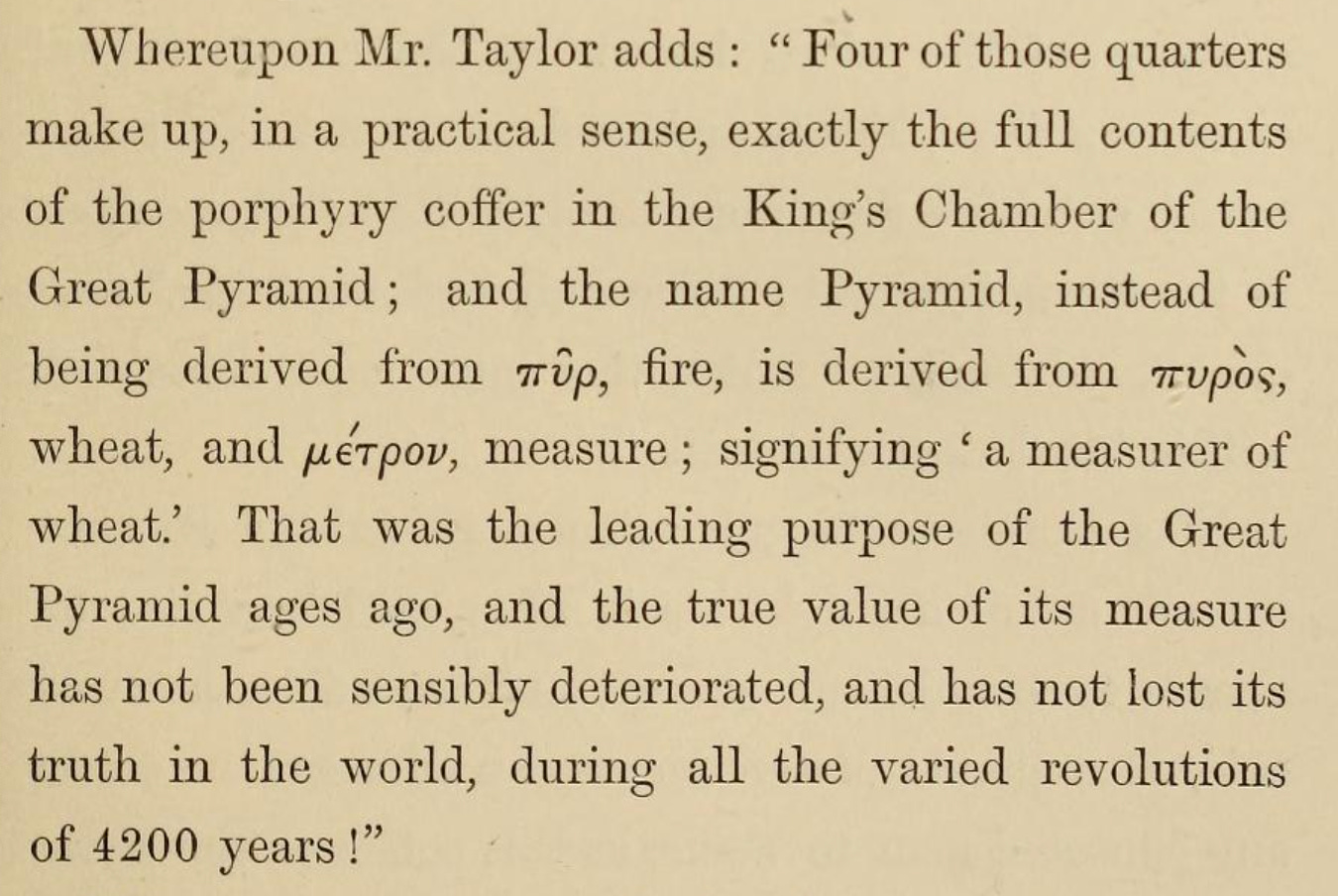

Smyth refers to the stone as highly polished and of a fine bell-metal consistency, in a sort of hard, compact, and faultless porphyry. Eusebius cited Porphyry. Look at the meaning of the name: Purple-clad. As an igneous rock, it was a prestigious Roman sculpture material.

I’ve demonstrated Rome was quazi-Etruscan all the way up to the 1st century BC, as evidenced by Etruscan statues with Etruscan writing from Rome, dating to this period.

According to the Latin poet Silius Italicus (Punica, VIII, 483ff.), the Romans got their official insignia from Vetulonia, “And Vetulonia, the pride, once, of all Etruria. That city gave us the twelve bundles of rods that go before a consul, those twelve axes with their silent menace, she first adorned the high curule chairs with ivory, and first trimmed official robes with Tyrian purple; while the bronze trumpet that stirs the warriors, that too was her invention.”

All of this indicates an Etrusco-Roman era in Egypt that was ignored by Egyptologists and historians, or if not ignored, too subtle to warrant more scrutiny, as these artifacts could be forgeries or Egyptologists may be overwhelmed with the amount of material left by the most recent cultures to inhabit that region, which were of an oriental disposition. Egypt was known as the Granary of the World. The following is an account of what the word pyramid could be a corruption of. Rather than fire, or pyr, it could be wheat, or pyros, which is the same word only one without the Greek termination. Either way, this affinity is important.

For those interested in diving deeper into these subjects, invest in the Spirit Whirled series and The Real Universal Empire.

Become a member to access the rest of this article.

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to Ancient History, Mythology, & Epic Fantasy to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.